THE BIGGEST YAMAHA RETURNS FROM A YEAR ABROAD - POLISHED, POISED AND EVEN MORE POWERFUL

YAMAHA FJ1200

In 1984, Yamaha reentered the super-bike fray after years of neutrality. The long-awaited FJ1100 was big, last and refined - the first open-class street bike from Yamaha to be taken seriously, an immediate force to be reckoned with by the other factories. There were faster, sharper bikes that year, but none of them had the FJ’s whole-cloth competence. The Yamaha embodies a classic balance of comfort and performance that has lengthened its lifespan far beyond that of the other open-class soldiers it once fought, which have long since faded away.

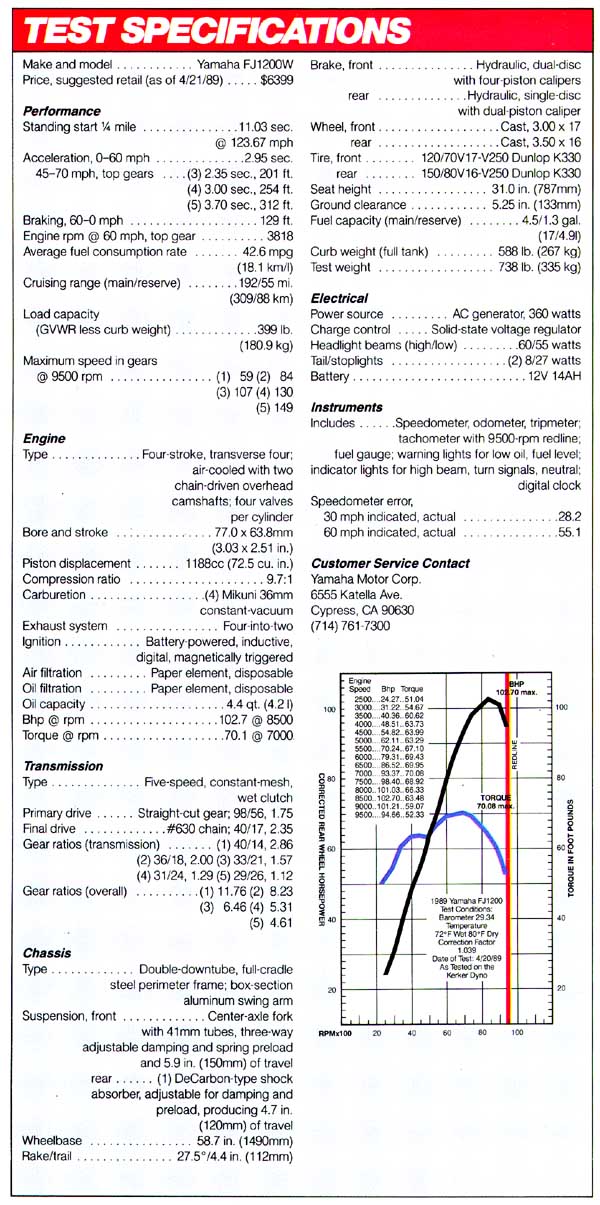

Since 1984 the deck has been shuffled more than once: positions and players have changed. In the natural progression of things, the FJ has gone from warrior to elder statesman. Pulled from the U.S. market last year due to a surfeit of unsold 87 models, and now returned from exile, the FJ is no longer the flagship of Yamaha’s engineering acumen. Instead, Yamaha has sharpened the FJ's focus on the sport-touring market, where it now competes with such machines as BMW's K100RS, Suzuki's 1100 Katana and Kawasaki's ZX-10.

Other liter-class motorcycles make more peak horsepower and handle better than the FJ, but it has taken on a smooth, gray-at-the-temples character those adenoidal upstarts lack. The Yamaha's beauty becomes apparent as its odometer racks up miles. Many motorcyclists will be hard-pressed to find a more comfortable bike for a rider and passenger, short of a full-dress tourer. It's still one of the hardest-accelerating motorcycles around, and well considered suspension upgrades have seen to it that the FJ's legs have more than enough life to run with the rookies.

In fact, the only things that stop this bike from still being the Superbike King are Yamaha's own FZR1000 and Suzuki's GSXR-1100. But those are birds of a much different feather, with more emphasis on high performance and less on utility. The tightest of them (the FZR) weighs 66 pounds less than the FJ. Their more modern engines make greater peak power that results in higher top speeds, and they have more advanced chassis. But strap your significant other to either of those brutes for more than 50 miles and it's only a matter of time before papers are served.

The FJ can still bang fairings with the youngsters, up to a point beyond the limits of most riders, but experience has taught it certain things that come with middle age. It has learned to, well, prolong the act of riding. Rather than going at a full-throttle, toe-curling sweat to completion of an outing in the shortest possible time, the FJ wants to satisfy its rider over a period of hours, over hundreds of miles.

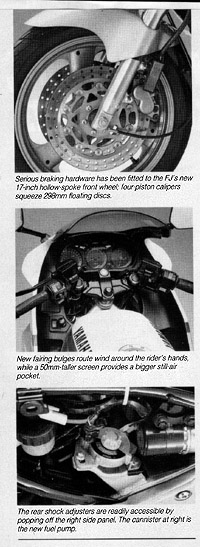

In fact, long-distance riders not of the bolt upright, full-dress school may find the FJ more comfortable than the land yachts. Set full soft, it rivals their cushy rides, easily absorbing a variety of bumps, holes and ripples. The fairing and windscreen - 50mm taller and 60mm wider this year, with bulges to keep windblast off the rider's hands - encapsulate an average-height rider's torso in still air. The seat is thick, wide, and feels lower than its 30.1-inch height. Wide and high clip-ons cant the rider slightly forward, while rubber-mounted footpegs place his feet slightly to the rear. Overall, the FJ offers splendid accommodations.

In keeping with the bike's enhanced emphasis on long-haul comfort, backseat riders have been granted rubber-mounted footpegs and a less pronounced slope to their portion of the saddle. One veteran passenger gave the Yamaha high marks, faulting it only for a still-too-steep perch which slid her insistently forward.

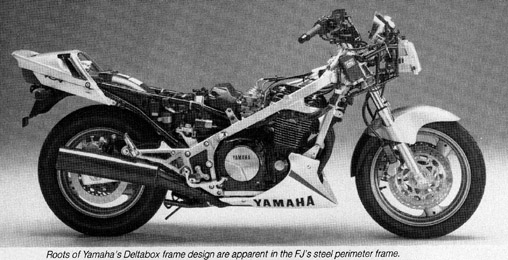

Weight and sheer size are the major chinks in the FJ's armor when it comes to backroad battle with newer liter-bikes. At 588 pounds wet, it's considerably heavier than the modern repli-racers; the FZR 1000 weighs 522 pounds, the GSXR 100 weighs 532. The FJ's wheelbase stretches to 58.7 inches, while the biggest FZR's wheelbase is 57 inches, and the GSX-R's a stubby 56.7. All other things being equal, a shorter wheelbase makes for a nimbler motorcycle. Still, at speed, the FJ seems smaller than it is, and feels light on its feet. Aggressive riders, though, who like to flick into corners, will find the steering a little on the slow and heavy side.

In the sport-touring venue, the FJ's weight and size hurt it not at all. Over a long haul the bike's mass makes it feel like a 7-series BMW automobile - totally relentless and unruffled, solid as a very supple rock, the smoothest of engines begging for more throttle.

The Porsche-like dashboard further reinforces the FJ's image as a Euro-cruiser. Three large instruments - a tachometer surrounded by a speedometer and a fuel gauge - light up a warm and readable orange at night. There's also an easily accessible fuel-reserve switch in the left-side fairing inner. A digital clock keeps track of the time; not such a small thing when you need to know but your watch is buried under your left sleeve and gauntlet. Remove the bodywork, and it reassembles with solid, logical precision. Everything about the FJ says function without frillery. Here we are. Let's you and me snort some road. Fuel capacity of 5.8 gallons gives the bike a range of about 250 miles, longer than that of most riders.

A few minutes with a screwdriver and a 14mm wrench turns the same bahnburner into a capable swerve-blaster. The FJ has what Yamaha refers to as "programmed suspension" at both ends. Twisting the fork's three-position spring preload adjuster also alters rebound damping (and compression damping, to a lesser degree), or damping and preload can be adjusted independently. The DeCarbon-type rear shock has some of the most accessible adjusters on the market; pull the seat, pop off the right side panel and they're right there. Twisting the preload adjuster turns a sprocket and a tiny chain that crank the shock's preload collar up or down, while adjusting damping accordingly. As with the fork, the shock's preload and damping can be set separately. The shock adjuster offers five numbered positions, with quarter-steps between each one for a total of 17.

The single-rate rear spring is 18-percent stiffer for '89, and the shock's linkage has been rearranged for more-progressive action. Fork springs are dual-rate items as before, but both rates are now approximately 15-percent stiffer. Yamaha says it was after "increased sport-bike feel." We say the change compensates for the underspringing of previous FJ's. Stiffer springs also brought a welcome increase in ground clearance. You have to ride the FJ hard to grind away the footpeg feelers, and very hard to nick the centerstand.

With the rear spring at the third position and damping at the fourth, fork spring preload in the second setting and damping at the third, Cycle's fastest expert found the FJ entirely trustworthy, if somewhat cumbersome, around the tight streets of Willow Springs racetrack. Although that track is a relatively smooth one, the FJ's heft actually helped filter out what bumps there were, and it does likewise on bumpier backroads. Since the unsprung weight (wheels, tires, brakes) of a big bike isn't usually much greater than that of a small one, such weight accounts for a smaller proportion of the larger bike's total. As a result, suspension inputs affect the mass of the larger bike less. Bumps don't upset the FJ, making it an unshakable platform upon which to flail away at handlebars, levers and tarmac. The big Yamaha is wonderfully stable in a straight line, too.

That excellent stability results in part from replacing the old 2.75 by 16-inch front wheel with a lighter, cast-aluminum hollow-spoke 3.00 by 17-inch wheel and lower-profile tire. The rear is also a hollow-spoke design, but in the same 3.50 by 16-inch size as before.

The diameter of the low-profile, 70-series, 17-inch Dunlop K330 front is within millimeters of that of the 80-series 16-incher it replaces. Rake and trail remain the same at 27.5 degrees and 4.4 inches, as do the Kayaba fork's 41mm stanchion tubes. But the bike feels more stable, at least partly because the 70-series tire has less sidewall to flex.

Tire choice greatly affects a sport-bike's feel. The FJ was originally designed around 16-inch Pirellis purpose-built for Bimota. The front tire, although designated a 120/80, was actually 128mm wide. That tire's width and profile created steering torques that tried to stand the previous FJ up abruptly when braking into corners. It also contributed to the bike's unwillingness to change lines in mid-corner.

The new 17-inch front Dunlop, though also designated a 120, is considerably narrower at 117mm, and helps the FJ's steering considerably. The tendency to stand up under braking while leaned over is much less pronounced, and the bike changes headings in mid-corner more readily, although it still requires more effort than do modern superbikes. Overall, the new tire makes the bike feel more precise, and minimizes its handling quirks at the bargain cost of a minor increase in steering effort.

While fitting those new wheels, Yamaha engineers decided to graft on new front brakes, as well. Larger, 298mm floating discs replace the old 280mm solid-mount rotors, and they're squeezed by four-pot calipers in place of the previous model's twin-piston units. Yamaha's ineffectual anti-dive has been shown the dumpster and is rarely missed; especially now that spring rates are stiffer. The radially vented rear disc is unchanged, and is still one of the best rear brakes around, offering excellent feel and power - especially with a passenger. The brake upgrade doesn't necessarily allow the bike to stop any faster but the '89 does require less effort, and feeds back reliable information.

Some things never change, thankfully. This motor will still leave bruises on your heart from constantly banging it into your spinal column. A regimen of gradual refinement has made it even stronger throughout its rev band. Displacement increased to 1188cc with 3mm-large bores in '86, and the '89 FJ improves or that engine with a more precise, digitally controlled spark-advance unit. A new electric fuel pump satisfies the 36mm Mikuni constant-vacuum carburetors, which have one-size-leaner main jets for fewer nasty emissions.

This is a civilized motor. Yank the fairing-mounted choke knob to its stop for initial fire-up, and the FJ immediately assumes a dignified 1200-rpm idle - none of this 4000-rpm-or-nothing stuff that grates on the sensibilities of the mechanically sympathetic.

Below 3000 rpm, the air-cooled, double-overhead-cam, 16-valve engine sounds semi-agricultural, with no water jacketing to absorb noise. Vibration through the grips is readily apparent low revs, up to about 50 to 55 mph in top gear; it's not particularly bothersome unless you have to ride that slow for while. By 60 mph, wind carries away whatever sounds the engine might be making. The FJ has a top-gear sweet spot from 65 mph up to the vicinity "go directly to jail," and its mile-wide powerband means there's a deep, easily tapped pool of acceleration anywhere within that zone. Deceptively smooth and quiet - ticket-prone, in other words - it's a bike your insurance broke and lawyer will love. Around 8000 rpm the smooth engine again becomes a bit buzzy, and in top gear the FJ can't hurl itself forward from 120 like superbikes of more recent vintage.

The new FJ runs nearly identical quarter-mile times as Cycle's original FJ1100 clocking a best of 11.03 seconds at 123.7 mph, to the '84's 11.07 seconds at 124.8. An '86 FJ1200 Cycle tested ('750s vs. l000s," July 1986) ran 10.78 at 127.1, with one horsepower less than our original FJ1100. What that proves, again, is that the last tenths of quarter-mile times are highly dependent upon rider skill and weight, traction on a given day, wind, humidity and the position of Jupiter's moons.

At everyday speeds, the FJ1200 is simply a phenomenal performer. Let's talk roll-on acceleration from 45 to 70 mph. Pay attention here: With the exception of the 88 V-Max Cycle tested - and only in third gear, mind you - the FJ's roll-on numbers are better than those of any production motorcycle we have ever measured. The V-Max beats the FJ in third gear by two-tenths - 2.15 seconds to 2.35 - but the FJ outmuscles the VMax by 0.25 second in fourth and fifth. The FJ is faster in roll-ons than both of its predecessors. Faster than the FZR 1000. Faster than either of the 1100 Suzukis. Faster than the ZX-10. Fast enough to make you a speeding bullet. Yamaha, pursuing peak power with its five-valve Genesis design, has apparently decided upon a different role for the FJ1200, that of designated torque-monster.

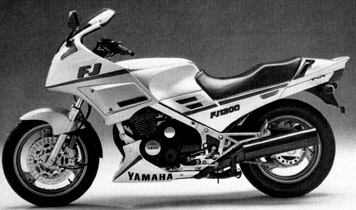

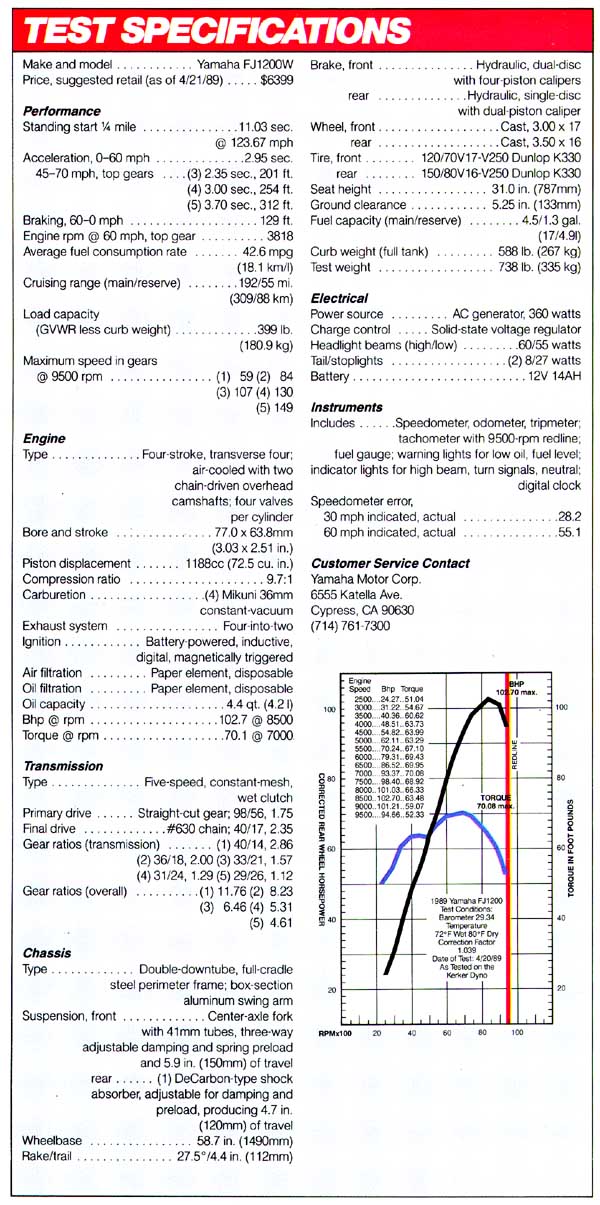

The FJ powerplant does more before 3500 rpm than most engines do all day. At that engine speed, 60.6 foot-pounds of torque are available. The FZR1000 can't work up to that until 3000 rpm later. As to horsepower, at engine speeds most common in street riding, the FJ buries the upstart FZR with 10 to 15 horsepower more all the way from 3500 to 7500 rpm. The FJ's 102.7 peak comes at 8500, right where the FZR's power curve steepens on its way to 114.9 horses at 10,000.

Such compelling power, combined with almost armchair-like comfort, makes it hard to fault the FJ in its role as traffic-blaster and road-swallower par excellence. Recruit a passenger, strap on some soft luggage, and try to conceive of a more pleasant long-distance, high-performance conveyance.

Time has been good to the FJ. It has fought its battles, and gallantly, but it is not nearly ready for retirement. The younger lions claw and bite harder, and their lifespans will be short if history is any indication. Yamaha's FJ1200 is a survivor because it is an intelligent machine, one with wisdom tempered by fire. Rather than doing one thing excellently, it does everything very well.

Reprinted without permission from Cycle Magazine, July 1989.